Hello Friends,

This past week, I have finally returned to my novel, which feels like a mountain of work. I know the only way back in is to let myself play with words and scenes and characters, to take the work seriously, of course, but to be sure not to take myself and my role in the work so seriously; in other words, I need to be able to create a playful relationship with my draft, as a way back into something that feels daunting.

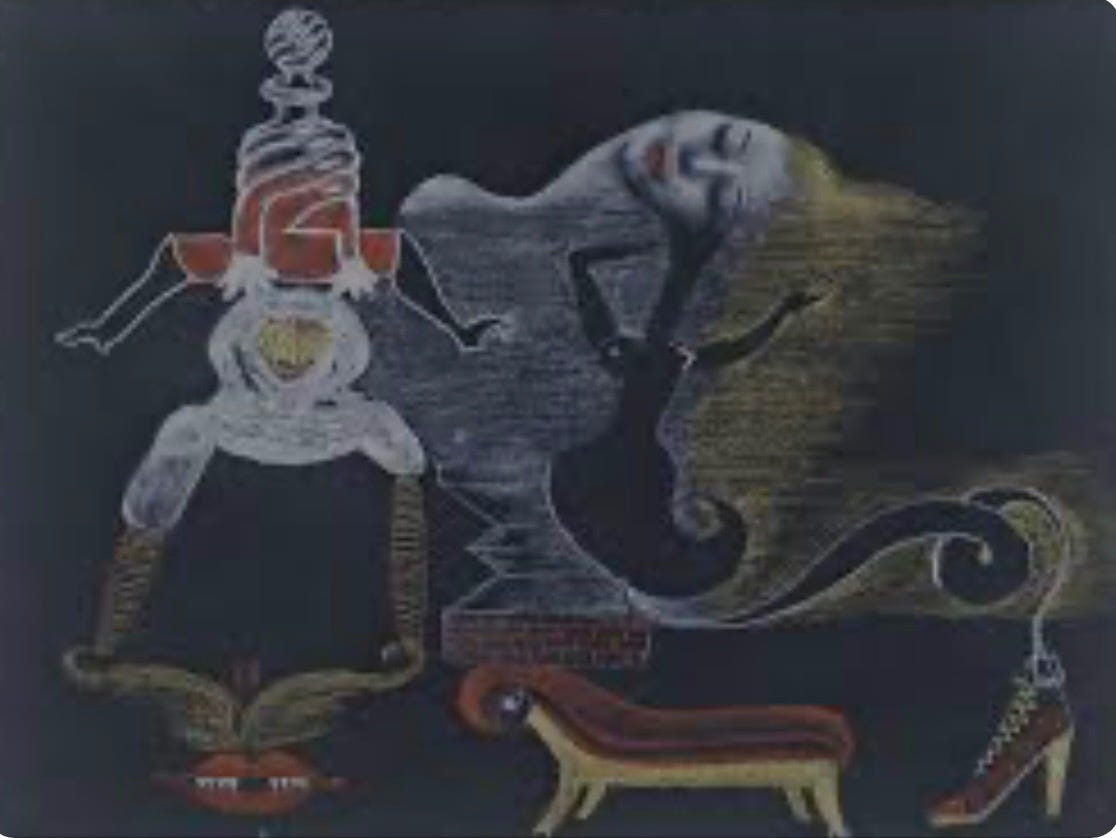

I’ve been thinking about writers and artists from the past who have been more focused on aspects of play, who didn’t worry so much if they were making logical sense or if their paintings depicted reality, and of course, my mind wandered to the Dadaists of the early 20th century.

Dada was an artistic revolt in Europe and New York from 1915 to 1923 (started in Zurich by sculptor Hans Arp, filmmaker Hans Richter, and poet Tristan Tzara). Dada was a post-war revolution, protesting traditional beliefs of a pro-war society, and to a lesser degree, fighting against racism and sexism. In order to achieve these aims, writers and artists eschewed traditional ways of making art, resulting in a playfulness both on the canvas and the page. Dadaism cleared the way for the later Surrealists, including Salvador Dalí.

Tzara suggests this way of making a Dadaist poem on one of his Dada manifestos, which is the making of meaning through a game of chance:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to 52 Writing Prompts to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.